Céspedes and his inexperienced fellow-believers proclaimed Independence at Yara, without any supply of arms or munitions of war, without provisions, clothing, &c., &c., with which to support their movement. Ignorant of what revolution is, they launched forth just like children who heedlessly play with a wild beast, in entire ignorance of its nature. The first moment of enthusiasm, on the part of the peoble (sic), and of surprise, on the part of Government, gave them the victory at Bayamo; and they at once thought that the Independence of Cuba was already secured. This was a fatal error, a sad illusion, which blunted their common sense and gave loose rein to their passions. It was the fatal error of those men who had not sufficient strength of will to be able to wait. Ah! how fatal it is not to know when to await!

The camagüeyanos were aroused at the enthusiastic shout for liberty, and they wished to help their brethren of Bayamo, driven on by a sentiment of fraternity and by their yet stronger love of liberty; —that noble aspiration which God has imbued in the hearts of all men. I shared not in these desires, although I did really in their sentiments, but I was restrained by experience and by my knowledge of the situation. Anxious to be of service to my country, I offered to go to Bayamo as a representative from Puerto Principe, which I did.

From my first steps into the Eastern Department, I was convinced of the error into which the people had fallen, and the impossibility of keeping up so unequal a contest. Moreover, after studying the revolution and sounding the feelings of the people, I discovered that they did not desire the movement but had been dragged into it; without noticing, in the beginning, owing to their blind precipitation, that they were not prepared to secure a successful issue.

In some private circles I spoke of the propriety of changing the cry for Independence into an acceptation of the Cádiz programme; —an idea which was well received and seemed so to change the course of affairs, that I ran a great risk, being threatened by the few who persisted in their original intention. I spoke to Céspedes and made known to him the untimeliness of the revolution; that if he really desired the welfare of Cuba, this latter consisted in withdrawing from a war that must be ruinous and unsuccessful in the end; that the liberties offered in the Cádiz programme were perhaps even more than would suit Cuba, &c., &c. Céspedes, convinced by my reasoning agreed to my proposals; and if he then failed to follow my advice it was, to use his own words, because he feared that he would not be obeyed by those who had already proclaimed for Independence. They did not understand the true policy that should be followed in the guidance of nations. They began badly and will end worse.

On my return to Puerto Principe I found the country in insurrection, dragged on by two or three men who were led wrong by their ill-digested ideas of liberty or by their own private interest, and whose only wish was revolution in whatever way it could be brought about. I grieved at this mistake, but without losing heart; and, always firm in advancing the prosperity of Cuba, I called a meeting which was held at Clavellinas. There I made known the result of my observations during my trip to Bayamo; and, after some discussions, the force of my arguments prevailed. With one exception, all agreed that we should adhere to the Cadiz programme. I was afterwards appointed General-in-Chief with especial charge (thus was it set forth in the record) that I should have an interview with General Valmaseda for the purpose noted above.

In a conversation with that gentleman, he manifested the best of intentions in favor of a pacification but stated that he was not empowered, by his government, to make any concession. He offered, nevertheless, to grant effectual ones, so soon as he could obtain the power. He called my attention to this; that whatever the liberties which should be granted to Cuba, the rights of the cubans would have to be regarded as attacked, if they did not send representatives, to have a hand in everything that might be done in regard to this country.

I knew too well the reasons of General Valmaseda, but fearing that my fellow-country-men might not seize the force of his reasoning, we agreed upon a truce of four days, which I requested, in order to call another meeting more numerous, and one which should decide upon the matter. This meeting took place at Las Minas; and there, as well as at Clavellinas, the majority was not for a continuation of the war but for accepting the Cádiz programme. Had a vote been taken, it is certain that this choice would have carried; but I refrained from calling a vote in order to be consistent with the Caunao district, which had made known, through its delegate, don Carlos L. Mola (Junior) that it wished to have no voting; because, in case thereof, they would be bound to its result; and that district was only in favor of accepting whatever the government chose to grant them.

An immense majority was in favor of the programme: and, nevertheless, the war was kept up, because those, bent upon it, spared no means nor suggestion to entice away those in favor of the Cadiz programme. That is to say that, taking advantage of family ties, of friendships, and of an ill comprehended association, &c., &c., they dragged along with them the unwary and the inexperienced, who were then reluctant enough and who now know their error. As I never wished to force upon anyone (not even on my own brothers) my own ideas, nor to make use of any other means than persuasion, in myself merely with enlightening the people, showing them the mistakes into which they were led by those who were interested in the continuance of the war.

I have not sought to impose my notions on anyone, but I do not, any the more, accept those of others, when my reason and my conscience reject them. And I believe there is no right, for law, nor reason to support those who willingly, or through force, whish (sic) to force upon others their own ideas, however good or holy these may be.

Those who are at the head of the Cuban Governement and guide the revolution believe their triumph possible; they think their ideas are correct and their way a good one. Very well; but, not believing as they do, I move aside from that government, whose pressure and arbitrariness are such, that it will not even admit neutrality in others. I will not wage war against you; I will not take up arms against you, except in personal defense; but I separate from men who wish to impose their own notions on others through force. You are free to think and act as you like, and I reserve to myself the same right, and act in accordance therewith.

But there is more. In the position where, unfortunately and much against my will, events have placed me, I occupy a place as a public man, as a politician, in Cuban politics; and I should not remain inactive while I behold the destruction of Cuba, and look out merely for my personal safety under the protection of the Spanish Government. No, Gentlemen, I would then be a bad patriot, and I love my country before liberty, or rather I do not understand the former principle as divorced from the latter. Both are intimately found together; and, in order that the first be worthy, honorable and beneficial to humanity, it cannot be separated from the second.

I am a Cuban, the same as yourselves, and I have consequently the same right to busy myself with the welfare of my country. Let everyone have his method; you pretend that you obey the popular will; that you are at the head of government, because of the will of the people and popular choice: that you act in conformity with ideas and sentiments of the Cubans; and, finally, that you are promoting the welfare and prosperity of Cuba. I shall prove entirely the contrary.

The favorable reception, with which my ideas were met at Bayamo, the meeting at Clavellinas, that at Las Minas, and the desire, —almost unanimous, —to accept the concessions offered by General Dulce, prove sufficiently that the country wanted peace; nevertheless, you maintain war. Hence, popular suffrage in the country is but, a chimera.

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes

Let us see how the actual government was formed. On the one side, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes who, for himself and in his own name, set himself up as the dictator of Cuba, appointed a certain number of deputies for the East, at the famous meeting in Guáimaro. That is a fine representation of popular will and an admirable republic, when the deputies are not elected by the people. On the other hand, the assembly at Puerto Principe, was illegally constituted and entirely unauthorized; and, finally, some deputies from the Cinco Villas, —the only ones which perhaps held a legitimate representation, — met together and formed the actual government, which they should have called the Venetian, rather than a Cuban Republic. They formed the government by sharing with each other the offices, and they propose thus to shape the destiny of Cuba. A handful of men, thus representing over a million souls, who have had no share in their nomination, does not assuredly constitute popular election.

The Cubans want the liberty of assemblage, freedom of speech, respect of property, personal security, the liberty to leave the territory of the Republic, —which is a right secured in all nations of the world to every individual; they want, in fine, to be governed as the majority choose, and not according to the will of a few. But nothing of all this is done. Whoever puts forth ideas contrary to those of the government or of any of its functionaries, is threatened with four shots; property is a prey to the first comer, who, with arms in hand, can take possession of what suits him; the lives of men are sported with, just as children sport with flies; and in fine, whoever attemps to abandon the government, even without intending to wage war on it, is persecuted unto death. Hence the conduct of said government is not in conformity with the ideas and sentiments of the country.

If to all this be added the arsons and the complete destruction of Cuban wealth, the demolition of towns and… what must follow in the end, can there be one sensible man, who will maintain that all this constitutes the prosperity and well-being of Cuba? Assuredly not.

You employ force, deceit, terror to drag the masses on and carry out whatever you judge beneficial for the cause of Cuba; I use only reason, truth, and the irresistible logic of facts and of experience, not the material argument of arms.

Domingo Dulce y Garay

Well then, knowing as I do, that the country does not want war and that it continues therein under the pressure of the Cuban government, on the one hand and, on the other, out of fear of the punishment which the Spanish government might inflict; knowing, as I do, that nothing is to be expected from the United States, as it was attempted to make the people believe; knowing that, since the beginning of the insurrection, 40,000 men have come from Spain, and that many more will come —a fact generally unknown in this country; aware, as I am, that over 100,000 men are under arms; that the coasts are well watched, and that the New York Junta lacks ressources to send material aid to the Insurrection; aware, moreover, that the Cuba, the Lillian, the expedition of Goicouría and others are lost resources; that the Insurrection is almost stifled in the East and in the Cinco Villas; that in the Vuelta-Abajo, far from there being any secessionists, it is the country-people themselves who pursue the insurgents, as has just taken place in Güines knowing, as I do, that the families, to be met with in the fields, are anxious to return to the towns; and aware of the importance attached to my conduct, both in the Island and abroad,I have made a new sacrifice for my country. I have come forward with my family; to prove, by my example, that I do not believe in the triumph of the insurrection, nor do I fear the Spanish government; which, animated as it is with the best of wishes, is ready to draw a veil over the past, provided the country can be pacified and many tears, much blood and loss of property be spared.

It is at sacrifice indeed, Gentlemen, for I expose my name to the evil tongued and make it the butt of false interpretations.

I believe firmly that the happiness of Cuba and the welfare of humanity, consist in the pacification of this beautiful country; and maintain this in the presence of the whole universe, with my hand on my conscience and head erect, as becomes a man of honor.

There is no man who is infallible, and perhaps my opinions and determination may be wrong; but I can at least affirm that I am acting in good faith, having for sole object in view, the welfare of my country and of humanity, and making total abstraction of my own personality, as well as of my own interests.

I am not a time server but a man of fixed principles; I am convinced of my opinions and feel the energy of my convictions, I now maintain what I have maintained since the beginning of the revolution, even previous thereto. My actual conduct is not therefore an apostasy, but the energetic continuance in my opinions and principles. These I do not mean to impose on anyone; I merely make them known inviting all to examine them in every detail, and I am sure that they will follow my example. But, if blind to reason and unmindful of the events which for a year and a half have supported my predictions, they persist in a struggle which I believe hopeless, let them keep on, but without extending the horrors of war to families. Let the women and children, whom government wishes to foster and daily supports with rations of bread, rice, butter, &c. come to the city; and let you keep on, if unfortunately, you refuse to listen to the voice of reason and of patriotism, in that senseless contest, which you must later repent having ever begun.

Reflect a moment; examine thoroughly, and not merely the appearances of the situation, and you will see that the existing strife is an unqualifiable mistake, and its continuation an unparalleled blindness. The country has been dragged into a revolution, which the majority repudiated — and not only the majority in number, but in the character of the persons. A small number, — very small indeed, an insignificant minority has dragged on the majority. Where was ever such a thing witnessed before, gentlemen? What has become of the intelligence of Cubans? Where are the energy and the influence of men of intelligence and character?

I know, and I am positive, that those of the majority think as I do; and nevertheless, they act differently, only because they lack resolution and are deceived by the few who are interested in keeping up the revolution, no matter by what means. The system, followed thus far, is deceit, and the result must be fatal. When a building is erected on shifting foundations it must inevitably crumble. I have striven during the Insurrection, pertinaciously and without remiss, in disabusing the people so, that they could, knowingly and conscientiously, make a choice of what was for their interest; but as this method is diametrically opposed to that of some evil patriots, these latter have waged a bitter and unfair war against me.

Cubans! You have seen that I have always been a protector to the people; that I have tried to enlighten them, that they might have a participation in everything, and know what they were doing, so as to follow their own ideas and not be carried by others; but what has been the result? I was treacherously and illegally arrested, at the request of those few who wish to rule the masses; I was sentenced to death, and over twenty times have they tried to put an end to my life. And there are yet some who, in their waywardness, seek my blood. Natural sense shows clearly that, when an attempt is made to annihilate him who speaks the truth, who enlightens and never deceives; who instead of speculating on his fellow-countrymen and growing rich on the revolution, makes use of his own means to succor the masses (let all Yaguajay speak); who never makes use of any pressure to enforce his ideas; and head erect, as becomes a man of honor, who allows himself to be ruined from the neglect of his own interests, in order to give himself up solely to the welfare of his country; does it not show clearly, I say, that the attempt is made only because his adversaries have different pretensions and a different line of conduct from his? Now, what is the difference? It consists in violence, deceit, the use of force, spoliation of the neighbor, for one’s own benefit; it is despotism, based on the ignorance in which the people are kept. I have sought to have the country governed as it is its wish to be the governed, in accordance with universal suffrage; your government, on the contrary, pretend to rule it as they see fit. They state that they want liberty for the people, whilst the most cruel despotism weighs upon you. You know, unfortunately, but (illegible) well, that this is the clear and plain (illegible) for you suffer too many of its sad consequences.

The people are told that from the United States will come reinforcement and resources; that there are elements to spare for the continuation of the war; that the Spanish soldier carries a cartridge-box and wears shoes of rawhide, and is short of provision) that there are no troops, nor will any come from Spain; that the taxes are ruining the country, &c., &c. Well, I, who do not, against whom no one can cite a single act unworthy of a man of honor; in whom the Cubans have always had their last hope; and through whose veins runs the blood of real patriots, I tell you that all this is illusion, deceit, and a fatal chimera.

The government of the United States does not busy itself, nor can it, with the Cuban Insurrection. Look at Article 16 of the treaty of 1797, and you will learn that they cannot favor the Cubans in the least efficacious way, without failing in national dignity and exposing themselves to a coalition against themselves. That government is too polished and financially shrewd, to compromise itself in a war that would entail serious mischief upon its commerce; and, moreover, there are other motives that would be too lengthy to detail.

Elements to spare, are neither in the country nor in the hands of the New York Junta, who have made great outlays and now begin to assert that the Cubans should provide themselves with arms, by taking them from the enemy. The Spanish soldier is today better provided for than in ordinary times, and he has abundance of everything. From Spain have come 40,000 men, and millions would be sent, if necessary. There are no taxes; they have all been suppressed, even the tithe: the custom houses yield now more than in ordinary times; and if the country does not enjoy greater franchises, it is due to the situation in which it is at present. So you see that you are being deceived and, not only yourselves, but also the Junta at New York and the whole world, as I shall prove.

Manuel de Quesada y Loynaz

I have just read a manifesto of Manuel Quesada (sic), published in New York under date of the 8th. inst., in which he sets astray entirely the opinion that should be formed of the state of the insurrection. I shall tear off the bandage. He states that the Cuban army numbers 61,000; that there are here five powder factories; that fire-arms are manufactured here, as well as swords and bayonets; that there are thirteen public schools and thirteen churches; that 3000 shoes are made every week and 4000 hides tanned every month; that the soldier receives, for daily ration, beef, sugar, coffee, vegetables and rice at his discretion, tobacco, &c.; that there are many sugar mills, grinding for the state: that several warehouses are filled with tobacco, sugar, hides, &c., to the value of many millions of dollars, that the territory which is occupied by the Cubans in insurrection is in a cultivated and producing condition, such as has never before been witnessed, even during years of the greatest abundance; that thousands of percussion caps are daily made; that he (Quesada) left here under commission of importance, after having temporarily put Jordan in command, under instructions, as well as the other leaders, &c., &c., to an endless length. I address you, fellow-countrymen, who are there on the ground of this insurrection whence I have lately come. You all, as well as myself, know that all these things are false, entirely false.

Quesada states that he has gone to seek means and bring arms, with which to end the insurrection, but for what does he need them, if he has 61,000 men? Is it possible that it should not occur to the inhabitants of New York to ask him what need he has of more means, when he has so many thousand men? When he has over 20,000 arms and can make more, as well as powder and caps? Why has not that soldier of fourteen years campaigning taken possession, with that army, of one single town, at least, wherein to locate the government of the republic? Why has he not captured one single port through which to get aid, export the productions of the country, to the value of millions, and thus acquire a right to recognition as belligerents? Where are those schools? Where are those churches? Have those at Guáimaro and Sibanicú, which were burned by that renowned general been perchance rebuilt? Why are the soldiers unshod, or wearing strips of rawhide, if 3000 shoes are made weekly and 4000 hides tanned per month? Where is the abundance for the soldier? Where has he got coffee, rice, tobacco, &c.? Where are those sugaring-mills in regular running order? Where are those warehouses, that contain millions? Where is that rich growth when not only there is no cultivation going on, but government orders to destroy and lay waste the cultivation that was in existence? Where are those cap factories? Are a few samples of such caps to be taken for thousands? Then, as to the commission of Manuel Quesada and his separation from command, do you not know, as well as I do, that he was ignominiously deposed by the Chamber; and that, during his stay in Cuba, from his first arrival, his conduct has been blameworthy, under all aspects?

Well then, Cubans, this is the plan followed from the beginning of the revolution. They are deceiving you and our brethren in New York, as well as the whole world. For these reasons I say that the edifice is raised on insecure and imaginary foundations. For these reasons have I always tried to undeceive the country and let them see clearly, so as to prevent Cuba from sinking into the abyss wherein she is intended to be cast. Withal I have not been understood. There has been no lack of someone who, out of exaltation, and under the pressure of some sad aberration, has qualified my conduct as treasonable. Ah! Whoever stated that knows not even the meaning of his words! When did I ever recognize this government? Never; but, rather have I always been in opposition there to. For as I wish my country’s welfare, I could not second an illegal, arbitrary, despotic government that is annihilating our land.

They recognize their error, but they have not loyalty enough to confess it; they are aware that they are neither statesmen, nor lovers of liberty, nor patriots, and their consciences sting them; they know that I have always seen farther than they could, and more clearly; that all my predictions have been fulfilled; that I have been alone in maintaining energetically my principles, bearing up against all kinds of privation and danger; and they do not forgive me for these advantages over them; they know that my past and my present career have been free from all stain, and they do not forgive me for that.

Antonio Caballero de Rodas

Well, if to have thus behaved; to have made entire abstraction of self and my interests, to look after the welfare of Cuba; to have done harm to no one, but much good; far from having taken life, to have saved the lives of many, without distinction of nationality; to have respected always the property of others, and never have let my hand touch the incendiary torch; to forward pacification, when I know that the country needs it, and that, by it alone, can tears, blood and destruction be prevented —if to have done all this constitutes treason, ah! then I am a traitor; yes, Gentlemen, I am one and feel proud of it.

Your government claims to favor liberty for the country; why then does it not consent to freedom of oneʼs principles? Why does it not admit of neutrality? Why does it force people to take up arms without distinction of persons? Why has it always been opposed to speaking out in public? Why did it oppose the country’s acceptance, if it so chose, of General Dulce’s concessions! Why does it persecute to death whoever tries to separate himself from said government, without having any intention of waging war against it? Why? I will tell you. Because then there would remain in the camp of the insurrection only a dozen men; the only ones interested in the continuance of this war between brethren; this war of desolation and extermination.

I agree that there was reason for the Cuban people to complain and be resentful against the government that ruled them; but all this has changed, not only with regard to the institution but as to the manner of being, as well. I am myself an example of what I state. I presented myself to the Captain General who received me in such a way as to prove, by his manner alone, his good wishes; even if these were not confirmed by the conduct which he followed in the Villas and wherever he has been able to make the impress of his own feelings be felt. In his proclamation he offers a pardon to all who will present themselves; but as every medal has its reverse, so whoever fails to do so, must suffer the cold and inexorable rigor of the law.

Fellow-countrymen, my brethren, let us throw a veil over the past. Let us look to the future of our families and to the prosperity of our nation.

You know well how many persecutions, privations, and even vexations I have suffered. I forget it all and forgive, from my heart, all who sought my death and wanted my blood. I forgive all who, directly or indirectly, have offended me, of whatever nation or condition they may be. I sacrifice all, all, on the altar of my country, and for the welfare of humanity. Why do you not follow my example?

Brethren! let there be no more tears, no more blood, no more ruins! Return to your firesides and let a fraternal embrace unite forever both Spaniards and Cubans, and let us all together make of this beautiful Island, —the Pearl of the Antillas, —the Pearl also of the world. Cubans, I await you, and the undeserved consideration shown to me by the first authority at Cuba, which fortunately is held by señor don Antonio Caballero de Rodas, I offer to use in your behalf. For myself, I only seek the satisfaction of having always forwarded the welfare of Cuba.

March 28th 1870

Publicado, presumiblemente, en El Diario de la Marina.

El Camagüey agradece a José Carlos Guevara Alayón la posibilidad de publicar este texto. Transcrito a partir de un ejemplar digitalizado y disponible en Internet Archive.

_-_De_verzoeking_van_de_heilige_Antonius_(ca.1500)_-_Lissabon_Museu_Nacional_de_Arte_Antiga_19-10-2010_16-21-31.jpg)

Comentarios

Y. J. Hall

6 meses¿Napoleón Arango lo escribió en inglés originalmente?

María Antonia Borroto

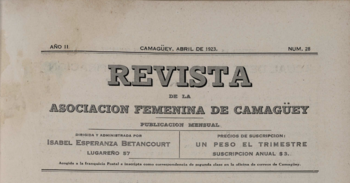

6 meses@Y. J. Hall: Es un llamamiento a los cubanos, así que, supongo, que debió circular primero en español. Ni siquiera (al parecer) se sabe con certeza la fecha de publicación. El investigador José Carlos Guevara, al publicar en el blog Gaspar, El Lugareño, una traducción suya de los primeros párrafos del documento afirma: "Carlos Manuel Trelles en el Tomo V de su Bibliografía Cubana del siglo XIX declara que, en algún momento aún por especificarse del año 1870, Napoleón Arango publicó un “Manifiesto” en El Fanal. Más tarde el bibliotecario confirma la existencia de un documento en inglés titulado “The cuban rebellion: its history, government, resources, objects, hopes and prospects. Address of General N. Arango to his countrymen in arms.” Se tienen noticias de su publicación, el 2 de abril de 1870, en el Diario de la Marina, pero en la colección puesta en línea por la University Florida Digital Collections no aparece en el referido número, lo que, por otra parte, no me parece raro, pues un documento de esa extensión y envergadura debió circular como suplemento. Me causa curiosidad el hecho de que exista una versión en Inglés de un texto destinado a los cubanos. ¿Se pensaba acaso influir también en la opinión pública norteamericana e, incluso, en su gobierno? ¿Se pretende contrarrestar la influencia de los agentes diplomáticos de la República en Armas en ese país?

Roberto Méndez

6 mesesEs un documento interesante, que no conocía y que me apresuro a guardar en mis archivos. El texto está tejiedo con unas pocas verdades, algunas medias verdades y muchas omisiones y hasta mentiras. Por ejemplo intenta hacer creer que casi todos lo apoyaban en la reunión del Paradero de las Minas, pero omite la fuerte réplica del Mayor que decidió el rumbo de la guerra. Cuando NA escribe estas justificaciones ya está totalmente vendido a las autoridades españolas. Gracias por mostrar este texto casi olvidado.

Leopoldo Vazquez

6 meses@Roberto Méndez: De acuerdo con Ud Sr Roberto.

Y. J. Hall

6 mesesEs un artículo muy interesante. Los mitos que definen a las naciones no incluyen voces disidentes, y mientras más años pasen, más difícil se hace revelar la verdad de una época cada vez más lejana. La experiencia me indica que muchas de las cosas que escribe Napoleón Arango tienen sentido. La realidad fue que las guerras de independencia devastaron la isla y causaron cientos de miles de muertes entre españoles y criollos; y, concretamente, los mambises nunca lograron vencer a España. Antes de la guerra, Cuba era la parte más próspera de lo que quedaba del imperio español. Siglo y medio después, España es un país rico y Cuba es uno de los más pobres del mundo. Y, por ironía de la vida, ahora todos los cubanos quieren ser españoles.

María Antonia Borroto

6 mesesUna vez que la localice, publicaré la réplica que a este documento hiciera Ignacio Agramonte, y verificaré si en sus cartas a Amalia lo menciona. Sería interesante constatar las reacciones que suscitó, tanto a favor como en contra. Fue un documento con amplia circulación y muy comentado. En PARES (Portal de Archivos Españoles) aparece registrado un documento, de 1870: "El gobernador superior político de Cuba ordena al teniente gobernador de Sancti Spíritus que tome medidas para que deje de comentarse en el periódico La Voz del Comercio, el manifiesto de Napoleón Arango, que allí fue publicado". O sea, se publicó también en Sancti Spíritus (me imagino que su versión en español) y, al parecer, algunos comentarios al texto en La Voz del Comercio resultaban incómodos. Lamentablemente el documento de marras no se encuentra disponible en la red, por lo tanto, desde Cuba me es imposible acceder a él.