Crossing the plain, you see smoke rising from behind the level line of the horizon, like smoke from a ship at sea. Presently it turns out to be the stack of a sugar central. But now and then off along the side of a field stands a row of royal palms, delicate and tall like a line of ladies at a dance. Coming to Camagüey, you see several massive and solid looking church towers, heavily buttressed, standing above the houses on the plain. It seems to be a completely colorless city and completely flat.

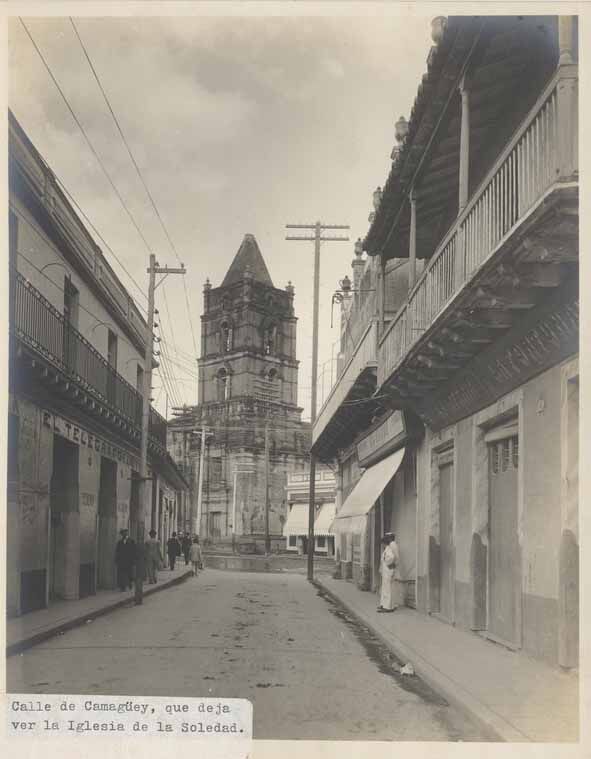

You are no sooner engaged in the labyrinth of narrow and twisting streets than you realize the city is not flat, either, but is built upon a slight rise, a sort of dome shaped elevation about a mile or a mile and a half long, on the highest point of which is built the great big church of La Merced with its high and massive tower. Unnoticed, along the bottom of this slight hill, a stream called the Río Jatibonico runs through its weedy trench, half dried up and choked with rubbish. But you wouldn’t know it was there.

Camagüey is an old city, and a big railway junction in the middle of a plain rich in sugar and cattle, and a city full of activity and a city full of churches. But it is the last thing in the world from a tourist resort: it is a working town. They do not know that tourists exist in such a town. If you are a foreigner they take it for granted you have come there on some job or other, for some deal with some estancieros [cattle ranchers] which will be consummated in the stink of cigar smoke, while their horses hang their tethered heads to the dusty street outside.

The town is full of cowboys and plantation riders and soldiers in colorless uniforms. Cowboys clank along bowlegged with boots and spurs and wide brimmed hats and faces like leather: guns in holsters hang at their belts, or machetes swing in great leather scabbards and beat against their calves as they walk. If they don’t have a gun or a machete, they will have a knife in a scabbard on their hip. But far from being fierce people, they go quietly about their business in the city, and then towards nightfall ride away into the plain again.

Nevertheless this is a grimmer sort of a place than Havana. There is less noise, less laughter, less light and many more people with all their front teeth pulled out. It seems to be a Cuban failing, to have weak front teeth: you see dozens of people, young men, young women too, walking about with only two canines left sticking out of their upper gum, and all the rest have been pulled out. They do not worry about getting false teeth, and besides, that is expensive. Camagüey is an active and industrious sort of a place, but a pretty poor one, too. In fact, at first, compared with Havana it seems terribly dingy and dusty and half ruined. It seems to be a strange and shabby city: or that was the way it looked at first to me. But that was because I arrived in the evening, and the street lighting is completely rudimentary: they do have electricity: but to light the streets they hang a naked bulb, the sort that would not adequately light a large room, up on a wire every two hundred feet or so along the street, and [they] let it swing and cast its feeble light upon the street. Then the houses are dusty and the streets narrow and the dimly lit shop windows are full of no splendor but necessities, and as cheap as possible, too. With all that the place is very crowded, but not animated in the way Havana is. So naturally the first night I came there I thought Camagüey was rather dingy, and didn’t know whether I was going to like it much.

Besides that, I had been depressed by a misapprehension about the Church of the Virgin of La Soledad. It is a great big important church right in the middle of the town, in the busiest part of it: but as I passed it, it was locked up (as churches in Cuba are from one until about five-thirty every afternoon), and besides, the walls were in an awful state, great patches of plaster yards square had fallen off and exposed the brick underneath. Along the walls, too, hung tatters of old posters about movies and May Day parades and workersʼ meetings and elections. But worst of all under the tower, inside the ground floor of the church tower itself, a man had established himself and set up a flower shop: not that the flower shop wasnʼt pleasant. But I concluded that the church had been closed up for good and all, this great big church to the Virgin closed up and abandoned, allowed to fall to ruins. Or maybe this was a strong Communist town, maybe they had actually gone in and shot the priests and desecrated the sanctuary and nailed up the doors. The whole thing made me feel very miserable and sick inside, and I thought that this was going to be a very unhappy and wretched place to be in: and the sooner I got out the better.

As it happens, the reason for the shabby and half ruined appearance of the outside of the church is this (I found it out in my Terry’s Guide to Cuba, which tells you absolutely everything!): In Camagüey lived, or maybe still lives, one Sir William Van Home, a great Canadian capitalist, a Canadian railroad man who came to Cuba and was the one who got the Cubans to build a railroad on the island. That, naturally, was a good thing, not so much for travellers as for transporting sugar and other products to the sea where they could be shipped off to foreign markets. Van Home seems to be, from what the guidebook says about him, an interesting sort of a character, a sort of a crazy nineteenth-century capitalist with big and strange ideas and unlimited opportunities for putting them into effect, good or bad. He built himself a big house just outside Camagüey, and called it San Zenon de Buenos Aires. Saint Zeno, of course, was no saint but the stoic philosopher: and that, my God, is such a perfect symbol of everything I can think of about nineteenth-century eclecticism: it is the most completely eclectic name I can imagine. Think of how much it includes: it is full of the completely misplaced optimism of the nineteenth century, it includes admiration for Greece and for stoicism, and drags in a whole string of republican and Jacobin associations, as did the paintings of David: but then the really clever joke of tacking “San” in front of Zeno and thereby eliminating all but the quaint aspects of Spanish Catholicism, but bringing them in in full force that is the mechanism of a kind of Joycean wit, and all the more forceful because after all, it reflects and openly parodies the whole Christian attitude towards pagan philosophy, since the very beginning: first Plato, then Aristotle. Saint Zeno! Then add de Buenos Aires after it: everything in that from Bernardin de Saint Pierre, the Lakeists etc. to the idea of the Englishmanʼs house being his castle. Some name for an estate, and all the better if you imagine it as being on the gate of some little villa on Ealing Common.

Anyway, whatever Van Home did, this name he chose for his place suggests he must have been a pretty amusing sort. The condition of the Church of La Soledad today is, it appears, due to some silly romantic notion of Sir William Van Horne’s that it ought to be “saved from the restorer,” or “spared by the hand of the restorer.” (Note: Terry’s words, concerning the quaint and antique-that is, tornado stricken-appearance of the outside of the church are: “The unusual quaintness and age-old aspect of the high-roofed structure so appealed to Sir William Van Home that through his friend Father Marinez Saltage, the parish priest, it escaped the work of the restorer and stands as it was when completed.”)

Terry says that Sir William used his influence with the parish priest, his good friend, to bring it about that the outside of the church was not touched, but left in the lousy condition in which it still is, plaster falling off the bricks into the street, dirt, half torn posters and so on. This is supposed to be quaint, picturesque, that a church should give the appearance of being about to fall down utterly into ruins. Actually the church is very solid and is not falling into ruins at all: and the next morning, when I went inside, I found the interior very beautiful and neat and clean and imposing, too, with its huge arches as massive in their construction as the arches of Roman Thermae or of some medieval citadel. But finest of all is the sanctuary, with the steps leading up to it and, behind the altar, the mahogany reredos with the image of La Virgen de la Soledad in the center, in black robes and behind glass, for it is a miraculous image.

Out of the seven big important churches in Camagüey, five are dedicated to the Virgin, and of these, four are the biggest churches there. The Cathedral, Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, La Merced (Our Lady of Mercy), La Soledad (Our Lady of Solitude), La Caridad (Our Lady of Charity) and La Carmen (Our Lady of Mount Carmel). The other two are San Francisco and the Church of the Christo: but the three big churches that dominate the center of town, forming a sort of a triangle in which they share the whole heart of Camagüey, marking it out with their three tall towers, are the Cathedral, La Merced and La Soledad.

Of these perhaps the largest and most important is La Merced, the tower of which dominates the whole city. Next to it is a monastery which once belonged to the Order of Mercy, but which was later secularized and turned into a barracks and later left to go to ruin until the Discalced Carmelites took it over.

La Merced is another church with massive pillars and great heavy round arches made of tons of mortar and brick. Two flights of steps and two altar rails separate the sanctuary from the body of the church and lead up to the high altar itself, which is Gothic in style and full of gilt and silver and gold, too. It is quite new, since it was built to replace an older altar which a fire consumed, and it cost a tremendous sum which some lady bearing the noble names of Betancourt and Agramonte presented to the church.

The side altars are all Gothic, too, to harmonize with the high altar, and are done in coaba wood, but the figures of the various saints on each one are very poorly done: these include two unpleasant statues, one of Saint Theresa of Avila and one of Saint John of the Cross. The central figure of the Virgin on the high altar, however, is quite a good one. However, if you turn and look up into the choir loft, you can catch a glimpse of another very impressive black robed Virgin, Our Lady of Sorrows, the kind carried in Holy Week processions, standing in a glass covered niche and facing a splendid crucifix.

The monastery, which has a three-sided cloister which connects with the church, is occupied by Discalced Carmelites of the Province of Castilla la Vieja: and they are mostly Spanish, except I suppose they have some novices once in a while from Cuba: quiet and polite men in brown robes, all wearing glasses, happy to talk to anybody that comes along, and happy to show one around their monastery. They are lucky not to have been in Spain! One of them told me how many Carmelites there had been scattered or killed: it was some phenomenal number.

This monastery of La Merced in Camagüey by no means gives the appearance of a prosperous foundation. It is an old building, but in pretty good order. It has a two-storied and three-sided cloister the fourth side of which is taken up by the wall of the church. They found all the floors falling in when they came to occupy the place after its secularization, and they put in good new tile floors. The cloister is quiet and cool and pleasant, and surrounds a garden shaded by mangoes, palms, papayas and banana trees. There also grow a number of boxed plants that can be taken into the church and arranged up the flights of steps in the sanctuary to decorate the altar for a feast.

But the building is too big by far for the small congregation that lives there and takes care of it: they are only seven or eight priests and a few brothers and a novice.

That all Cuban life is public, and that privacy is completely lost in the overflowing of public life into the rooms and patios of private houses, takes all sorts of forms. Not only do people wander in and out of hotel dining rooms selling things: that is not unusual, hotels are public. Not only do small boys run in barefoot off the street into cafes and clamber up on the bar rail and ask for a glass of water (which no one ever thinks of refusing them), that is all right, bars are public, too. Not only do people throw open the shutters of their houses in the evenings and have not the slightest objection to your looking inside through one room into another and still another: the whole house has become public, and everything that goes on in it. This complete loss of privacy in the victory of public life over everything else extends to churches and confessionals: and no reason why it should not, either.

There are no confessionals with curtains and doors to them, no confessionals you close yourself up inside of or hide in. The reason for this is probably that they would be unbearably hot. The priest sits in an alcove that is open to the front, and on either side are grilles let into the side of the alcove. The penitent kneels down before this grille and says his confession through it to the priest. He is right out in the open, and in many churches the confessionals are right alongside of the pews, and I suppose if anybody wanted to listen to the confession they could probably hear most of it. Nobody is in the least concerned about it, however, and there is no reason why the average person should be. I guess if a penitent murderer wanted to confess without being overheard, he would be able to find some quiet confessional off in a dark corner of a church. And, I suppose, the nature of things in Cuba is such that, if you were really interested in your neighborʼs sins, life is so public that you would know all about them long before it came time for him to go and confess them to the priest.

There are, also, altars all along the side aisles of most important Cuban churches, and these are not there for decoration alone, or for a chance passer-by to pause in front of for a momentʼs devotion. Mass is said, some time or another, in front of all of them, particularly in front of altars to the Virgin of La Caridad, protectress of Cuba. They have no altar rails in front of them, and are not shut off from the church in any way. If communion is to be distributed in front of one of them, a pew will serve as altar rail. They do not only say Mass up at the top of the steps in the sanctuary, but also down in the body of the church, among the people. But I suppose there is really nothing in the least uncommon or extraordinary about that in a Catholic country. And this is one of the principal reasons why they have signs on the doors of many churches in Havana to ask parties of tourists not to come blundering in before nine-thirty or ten in the morning: they are just as liable to come in a side door and find themselves right on an altar where Mass is being said, and go trampling all around it in a great state of ignorant confusion.

In La Soledad there is a negro sacristan who not only serves Mass for all the priests all morning, but takes care of the church, and so forth. He walks about very busily, wearing spectacles and a white linen suit and takes his office very seriously. One morning, after all the Masses had been said and I thought the church was completely empty, I heard a tremendous racket, shouting and imprecations and violent words going on off on the other side of the church. It was the sacristan, who was furiously bawling out a little boy who was kneeling in front of La Caridad: he had brought a crazy looking fluffy white dog in with him, and the sacristan was commanding him to get the dog out of the church, but the boy won, because a priest came along and shrugged and said it didnʼt make much difference. The sacristan went away very sore.

Another protest against peaceful penetration of private by public life was a discreet and humorous sign I saw in the back of a Camagüey print shop. The shop, like all other shops, stores and so on, was wide open to the street, and in the doorway a group of people stood around with their hats on the backs of their heads, talking and laughing and spitting into the gutter. Back in the shop a sign on the wall read: “No haga tertulia en mi puerta” meaning, more or less, “Donʼt obstruct my door by holding lectures and debates in it.” But nobody paid any attention to that.

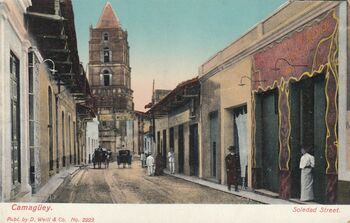

A proof that Camagüey is no center for tourists is the difficulty one has in buying picture postcards there. There is no sign of a card anywhere in the Hotel Camagüey, which is, in its way, famous, and is the hotel most likely to attract anyone who had come to see interesting and beautiful sights. You go from one place to another in the town, and no one has any cards. In one place they say they used to have postcards, but they forget what happened to them. In another, they bring out, not photographs, but little cards with tinted pictures of palm trees, of courtyards full of bougainvillea, or of big earthenware tinajones standing about by a door to catch the rain water. These cards are not postcards, but semi-precious remembrances to be carefully mailed in an envelope on somebodyʼs anniversary, I suspect. I went to the shop of the best photographer in Camagüey finally, and there they consented to sell me some old out-of-date postcards they had lying around. They said they were planning to make some new ones soon.

The Cuban landscape is not really tropical, although Cuba is a tropical country. By way of illustration, I will now record an imaginary conversation between two persons concerning the Cuban jungle:

A: Oh boy look at that jungle over there.

B: What jungle over where?

A: Over there, them woods.

B: Oh, over there, them trees.

That is the sort of conversation in which one might exhaust all the possibilities of Cuban jungle as a topic for enlightened discussion.

The Cuban jungle looks like any woods you might expect to see on Long Island except that the trees are smaller, and have some moss or other parasites hanging from them in grayish streamers, and are tangled up with more underbrush: but not a different looking kind of underbrush. Also, most of it, at any rate along the railroad and the Carretera Central, has been cleared away. Or maybe I didnʼt see any jungle at all: maybe I am only describing what I imagine would be the nearest approach to it that I saw.

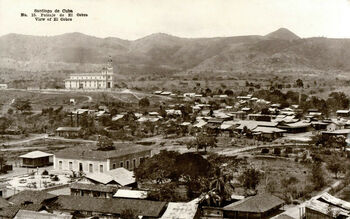

You ride along in the train, you come to a concentration of small trees and large bushes, and you say to yourself: ah, maybe this is the beginning of some jungle. Then right away the bushes thin out again, and among them you see half a dozen stray horses and cows, scattered about nibbling on the dry grass. When I say the Cuban landscape is not tropical, I mean it is not in the sense I mean it in no way resembles any pictures I ever saw of Yucatan, of Honduras, of the Amazon country, of the Congo country or anything of that sort. It does in parts resemble pictures of the grasslands of Nigeria, the Matto Grosso of Brazil, the Chaco. But where there are royal palms, it is just a nondescript landscape, fairly pleasant, of the kind one might associate with almost any part of South America. There is a whole lot of sugar cane, a whole lot of pasture land, and everywhere groups of royal palms with their graceful silvery white trunks stand around and shake their dark green heads. They are a pretty tree, and coconuts look like slatterns next to them. The land is mostly flat, except in Oriente and Santa Clara and Pinar del Rio where you get blue mountains standing in the distance like a promise of Eden.

The promise always looks better than its fulfillment. The mountains themselves are full of pretty valleys and royal palm trees and flowers, too, and streams: but from far away they really look fabulous. That is what they turn out not to be.

Another thing about the Cuban countryside is that you soon get depressed by the miserable bohíos, little huts thatched with palm or palmetto that stand in a stamped out dusty patch of ground where chickens scratch and naked brown kids play in the dust. These huts are where the poor live: and it is not picturesque. It is just lousy and miserable.

That is true also of the poor sections of towns like Camagüey and Matanzas and Santiago. The very poorest people live in bohíos in a sort of garbage dump on the edge of town. Those a little better off live in shattered stone houses among some torn up streets where pigs and chickens turn up and turn over and over the garbage in the gutter and turkey buzzards wheel in hundreds in the hot sky. Outside of Havana, the cities are made up of streets and streets of such houses, dirty little one- story houses with dust blowing in and out the door and the gray stucco falling off into the street. Nevertheless, from the attitude of the people that live there you get the impression that they find life easier and better and happier than the poor in the slums of New York. The poor in Cuba live in misery and dirt, but their poverty lacks the mental quality of despair which makes the poverty of northern cities so completely and horrifyingly squalid, crying out to heaven for vengeance. And, of course, in Cuba all kinds of fruits grow wild all year, and you never starve: nor do you ever freeze, either. It is supposed to be theoretically possible for every Cuban to get some kind of work, but that is just what people say. One thing is certain and that is that foreigners in Cuba are strictly forbidden to do any work there.

Just because the streets are dirty and channeled up where torrential rains have carved out gullies in the rainy summer time, and the houses are gray and shabby- looking in a Cuban city, doesn’t mean you are in a poverty-stricken neighborhood, either: you look inside the house, and you will see the upright piano, the picture of the Sacred Heart on the wall, the clean tile floor and the cool garden where two or three young girls sit in rocking chairs, with their braided hair and their white blouses and blue skirts, their school uniforms. These are houses of middle class families not rentiers, little shopkeepers, clerks, etc., who probably have less to live on than it would take to keep from starving in a New York slum.

Matanzas was the first place where I ever slept in a room with no glass in the window. The window was high up in the bare yellow wall, so high up you couldn’t see out of it. You pulled a rope and that swung open a big wooden shutter, painted dark red, that closed up the window if you wanted to shut out the light or the rain. But this was not the rainy season: that doesn’t begin until the end of May.

All through the interior of Cuba the houses do not have glass windows. They are protected, on the outside, by more or less fancy iron bars. Inside, you bar the window with wooden shutters. The purpose of the shutters is not to bar people’s vision that are outside: they are used to close out the hot sunlight. As soon as that side of the house is shaded again, the wooden shutters are opened. What does it matter that people passing in the street can look right through the house? It means air passes through the house, too: and also it means that your friends can see you sitting there, and stop and talk to you, while you can call out into the street without having to open windows, too. But the most important thing is for the house to be cool.

April, 1940. Camagüey

The Teatro Principal held three surprises for me in Camagüey. The first one was that the lights suddenly went up, after the movie was over, and I discovered that the audience was full of white suits and pretty dresses, and that, therefore, my dismal apprehension that the town was falling to pieces and dying of starvation had been an illusion produced by the lack of electric light in the narrow and silent streets. The third was that I discovered, from the top of the tower of La Merced, that this theater was a huge whale-backed place, one of the biggest buildings in town: the second was the most agreeable: the Mexican Vaudeville troupe of Beatriz Nolesca.

Beatriz Nolesca, the signs said, that I afterwards saw: “bailes, arte, juventud”. Dances, art, youth. What came on first was not youth but a middle aged Mexican Panurge, and I began immediately to laugh myself silly because I could just barely understand all his jokes, so that the pleasure at being able to understand them combined with the mediocre pleasure implicit in the jokes themselves to make them sound really humorous. But he was a good guy, and looked like a Marseillais, and his humor was the rhetorical miles gloriosus [glorious soldier] stuff the Marseillais make much of. Maybe I should not apologize for laughing.

He made a speech: then came three Mexican girls that looked like kitchen maids in everything, attitude, clothes, gestures and all, and did a dance with some big earthenware plates and some Mexican music. My curiosity about Mexico began to diminish rapidly, and yet I was gaga, fascinated by this dance. This was my first night in this strange town in this strange country and I did not yet know what to make of the place or any experience that occurred in it. I was open mouthed, like a cowboy in off the plain to see this same show, and I didn’t lose a gesture of the dance. I will never forget it as long as I live, it was so bad, it was so beautiful. Plates on one side, plates on the other side, they swing their heads to this side, to that side, sway, turn, plates here, plates there, smiling all the time. Tan tan tan, tan tan tan: the sort of music all tin strings and ought to have a marimba to it also! This way, that way. One girl was round faced, the other was really fat, the third was slim and had slim legs and a sort of a catlike face that was mean and pretty, and she knew she was more graceful than the others. Without there having been much clapping at all, they did a whole encore, the whole thing all over, just as a matter of routine, as if they had to do it twice. It was so pretty and so awful: this side, that side, turn, sway. Tan tan tan; tan tan tan. At the end they twirl around and up go their skirts like light bells around their

[blank space in the journal]

up on tiptoe legs. Ding Ding. The end. They run awkwardly off the stage. I never saw anything so lousy or so unforgettable or so fascinating. It wasn’t that they danced badly. They danced very well a dance that was so bad it made you want to cry, so bad, so meaningless. Some Mexicans!

It was even worse when the plump one came running out in a tight black short- coated furry man’s Mexican cowboy outfit, so black and tight and furry it made her look like a huge mouse, and all her movements were indeed those of a giant mouse, and that was what her smile wrote all over her face:

“Now you may see that I am a giant mouse.”

This was really more awful than the other, and with no good dancing to contradict the badness of the whole conception. I was transfixed by this dance: when it was over I could have wept.

Really the funny scenes were good. One of the sketches was about a machine for rejuvenating old men. This machine belongs to the owner of a beauty parlor and this panurge of a janitor who has been given half a share in it for back wages. An old woman and a young girl come in to have the girlʼs ninety-five years old fiancé reduced to a decent age: she wants him twenty, the mother wants him thirty. The panurge, after a lot of explaining about how the machine works, goes off, and comes back driving and whipping and kicking the old man across the stage and off the other side to where the machine is. You know that the machine rings a bell every time the man in it has lost five years. The bells start, count off some sixty years, and then start going furiously ding ding ding ding ding, while panurge comes dashing back saying he can’t find the switch, can’t find the key to get the old man out, etc. etc. Another interpretation of Huxley’s problem! Nothing is left of the old man but his black suit and hat. The reason for this is that the old man was the giant mouse dressed up in another costume. Or maybe the giant mouse was the daughter: I think not.

There was another sketch about a birthday party. The giant mouse had a birthday party. The sketch wasn’t funny, but the business in it was. A girl comes in with a great white dog under her arm and hands it to the other girl as a present. The dog is really just a little too big to be handed around, and it is funny. Then they say the dog’s name is “Como tú” [“Like you”] and they work that gag until it dies of exhaustion, then the dog barks and runs around and raises a lot of fuss and goes off. The real part of the sketch is to do with panurge, all gallant and important bowing and larfing and guzzling all the beer and dancing with all the ladies, each lady in turn fainting with great screams because she is overpowered by his body odor. All the dancing and fainting is very funny.

I went to see them again the second night, in a different bill, but they were not so good at all: there was something strangely disturbing in seeing those same gestures all over again even in different contexts. Both times, however, the giant mouse managed to be a giant mouse: and both times, after a dance by two girls (again with a plate, which one of them dropped, on the second night), Panurge came out and held up his hands to still the dying applause crying:

“Muchísimas gracias, respetado público, son mis hermanas las dos.”

“Thank you, thank you, respected public: those girls are my sisters.”

I suppose Cuba is too poor for a false feast like Mother’s Day to be much of a commercial success, and for that very reason, Mother’s Day has actually taken in Cuba. It is really something of a genuine feast, and it is certainly a religious one. It got mentioned from the pulpit, and you could see that it meant something to everybody, too. Mother’s Day is really a success in Cuba, a success which it can never hope to be in America, precisely because in Cuba it is useless to try and make it into a big advertising gag for candy and small presents, as nearly everybody cannot afford that sort of thing.

Instead of that, everybody goes to church and everybody wears a flower in his buttonhole, a red rose if his mother is living and a white one if she is dead, the red and white each having a meaning which was explained from the pulpit in the church of San Francisco. So you see everybody walking about loving their mothers: while in America the sale of candy and the amount of talk about loving one’s mother is out of all proportion to the actual love that is shared between mothers and their children. On top of that comes this great commercial insult, and so many other things of the same kind, that anyone with a grain of sensibility or decent feeling begins to wonder whether the love of one’s mother is not a false and shameful thing if it lends itself, without any protest, to the exploitation of charlatans. One immediately wonders why, if Americans really do love their mothers, they should tolerate for an instant that that love should be made a great buffoonery, and Mother’s Day is so cynically exploited in America that it is a perfect scandal: it makes people who really do love their mothers almost ashamed of that love on Mother’s Day if they happen to be sensitive to charlatanry at all. I do not insist that a half a million other perfectly happy people cannot love their mothers and go on loving them without being corrupted by Mother’s Day, and even giving Mother’s Day presents out of love and not out of compulsion or false emotion. But all that does not apply to Cuba. And probably if the truth is known they do really love their mothers in Cuba, and that is why Mother’s Day is a commercial failure there, but at the same time a great moral success.

This is not to say that there is not as much sentimentality about motherhood in Cuba as there is in America, but even then, the sentimentality in Cuba is rather more sound and fundamentally closer to a more important kind of truth about motherhood. Take the front pages of the Havana Post and El País on Mother’s Day, 1940. Of course most of the page is taken up by the German invasion of Belgium and Holland, a thing which demonstrates clearly that Hitler is diabolically inspired, is making war sheerly for its own sake, not even for the sake of conquest, but as an end in itself, his purpose being not to beat England and France without getting America in it, but, on the contrary, to get the whole world in the war again, to make sure the thing is really universal. Germany’s defeat does not matter, because he will then have ensured the destruction of the whole earth besides: it is a fundamentally diabolical instinct for mass suicide. However, to get back to Mother’s Day: the Dutch news cannot keep from the front page a certain tribute to motherhood: and it took typical forms in one paper and the other. In the Havana Post it was of course the silver haired old lady, sitting hunched up in a chair in a foggy, blurred sort of atmosphere so that you cannot see any of her features. That is the usual American version. Mother is wrinkled and frail but brave enough to bake a pie at the drop of a hat, and what America is really talking about all the time is grandmotherhood. Cuba, on the other hand, is not, and that is what makes Cuban Mother’s Day one stage less remote from the truth than the American Motherʼs Day: I therefore propound this rule:

Rule: When the Cubans talk about Mother’s Day and the love of mothers, they really mean mothers and not grandmothers: and also they really mean love, and not presents.

This is a fairly good thing.

Therefore the picture on the front of the País was under a headline saying: “Las Madres, fuente de la vida” or mothers the fountain of life, and showed a picture of a young mother with a lot of children around her, a very clear picture of a mother and her children all happy and smiling and having their arms around each other. Not a wrinkled up sweet old lady with no children, but mothers in as much as they are mothers, the source of life, not fountains of cookies and brownies and inexhaustible supplies of apple pie such as Cushman cannot hope to imitate. The sentimental reverence for fountains of life can also unquestionably be overdone, but it is so much harder to overdo something that after all has such a real importance! Life is one thing and apple pie quite another.

April 18, 1940. Camagüey, Cuba

This modern rat-race civilization having lost, at the same time, its respect for virginity and for fruitfulness, has replaced the virtue of chastity with a kind of hypochondriac reverence for perfect, sterile cleanliness: everything has to be wrapped in cellophane. Your reefers come to you untouched by human hands. Fruitfulness has no more meaning but has degenerated into a kind of sentimental and idolatrous worship of sensation for its own sake that is so dull it makes you vomit: the fat blondes in the dirty picture magazines are getting bigger and fatter and more rubbery, and all the people who think they are so lusty are really worshipping frustration and barrenness. No wonder they go nuts and jump out of windows all the time: such contradictions are completely unbearable and cannot be replaced by a lot of mental and sexual gymnastics, the way the mental cripples who have been psychoanalyzed seem to humbly believe.

There is more talk about Peace, Life and Fertility now than at any other time in the history of the world, especially, of course, in Germany and Italy (The Italian Fascists all talk like shrivelled up old men, mumbling between their gums, “Life, Life, Youth!”) and at the same time the people who yell loudest about all these things are clearly responsible for the worst war that was ever heard of, and are also busy putting out of existence in lethal chambers everybody that has gone crazy as a result of this kind of thinking (gone crazy, that is, without getting into the government).

April 29, 1940

The complete interpenetration of every department of public life in Cuba, the overflowing of the activities of the streets into the cafes and the sharing of the gaiety of restaurants by the people in the arcades outside, also applies to churches. There, the doors being open, while Mass is going on you unfortunately get all the noise and activity of the street outside going on, too: the clanging of the trolleycar bells, the horns of the buses and the loud cries of the newsboys and the sellers of lottery tickets. Outside the church of Saint Francis the Sunday I was there, a seller of lottery tickets was going up and down and shouting out his number with the loudest and strongest voice in the whole of Cuba, and Cuba is a country of loud voices. It was a fine sounding number, four thousand four hundred and four:

Cuatro mil cuatro cientos CUA-TRO,

Cuatro mil cuatro cientos CUA-TRO

and so he went on, adding some half intelligible yell now and then that had something to do with Saint Francis: probably that Saint Francis liked the number, too. Cuatro mil cuatro cientos CUA-TRO! You could hardly hear the communion bell.

All that is, perhaps, unfortunate. It is a shame that a lot of noise from the streets should fill churches during the consecration of the body and blood of Christ, but after all it doesn’t really make a tremendous amount of difference. It is unimportant because, after all, a person who is following the Mass is not distracted by it, and forgets about it altogether. Or if he is unfortunate enough to be distracted by it, it means that through some deficiency of his own, some lamentable lack of patience, some selfishness or other, he is preventing himself from following the Mass and is only thinking about himself.

And is it worse for there to be noise outside in the street than it is for there to be inattention and impatience and hearts and minds locked up against the sacrifice of the Mass inside the church itself? Which of the two dishonors Christ more? Is it a bigger shame that people should go about making noise in the streets, or that people inside the church should forget that Mass is going on and get angry at the people who are making the noise outside? But the problem doesn’t really arise, because you soon cease to pay any attention to the noises in the street. Havana is so full of street noises, and they penetrate everywhere, everybody is used to them.

As I came in the front door of San Francisco, a crowd of children, from the school I suppose, filed in one of the side doors two by two and began taking their places in the front of the church until gradually the first five or six rows were filled. Mass had already begun, and the priest was reading the epistle. Then a brother in a brown robe came out, and you could see he was going to lead the children in singing a hymn. High up behind the altar Saint Francis raised his arms up to God, showing the stigmata in his hands; the children began to sing. Their voices were very clear, they sang loud, their song soared straight up into the roof with a strong and direct flight and filled the whole church with its clarity. Then when the song was done, and the warning bell for consecration chimed in with the last notes of the hymn and the church filled with the vast rumor of people going down on their knees everywhere in it: and then the priest seemed to be standing in the exact center of the universe. The bell rang again, three times.

Before any head was raised again the clear cry of the brother in the brown robe cut through the silence with the word “Yo Creo...” “I believe” which immediately all the children took up after him with such loud and strong and clear voices, and such unanimity and such meaning and such fervor that something went off inside me like a thunderclap and without seeing anything or apprehending anything extraordinary through any of my senses (my eyes were open on only precisely what was there, the church), I knew with the most absolute and unquestionable certainty that before me, between me and the altar, somewhere in the center of the church, up in the air (or any other place because in no place), but directly before my eyes, or directly present to some apprehension or other of mine which was above that of the senses, was at the same time God in all His essence, all His power, God in the flesh and God in Himself and God surrounded by the radiant faces of the thousands million uncountable numbers of saints contemplating His Glory and Praising His Holy Name. And so the unshakeable certainty, the clear and immediate knowledge that heaven was right in front of me, struck me like a thunderbolt and went through me like a flash of lightning and seemed to lift me clean up off the earth.

To say that this was the experience of some kind of certainty is to place it as it were in the order of knowledge, but it was not just the apprehension of a reality, of a truth, but at the same time and equally a strong movement of delight, great delight, like a great shout of joy and in other words it was as much an experience of loving as of knowing something, and in it love and knowledge were completely inseparable. All this was caused directly by the great mercy and kindness of God when I heard the voices of the children cry out “I believe” in front of the altar of Saint Francis. It was not due to anything I had done for my own part, or due to any particular virtue in me at all but only to the kindness of God manifesting itself in the faith of all those children. Besides, it was in no way an extraordinary kind of an experience, but only one that had greater intensity than I had experienced before. The certitude of faith was the same kind of certitude that millions of Catholics and Jews and Hindus and everybody that believes in God have felt much more surely and more often than I, and the feeling of joy was the same kind of gladness that everybody who has ever loved anybody or anything has felt; there is nothing esoteric about such things, and they happen to everybody, absolutely everybody, in some degree or other. These movements of God’s grace are peculiar to nobody, but they stir in everybody, for it is by them that God calls people to Him, and He calls everybody. Therefore they do not indicate any particular virtue or any special kind of quality: they are common to every creature that was ever born with a soul. But we tend to destroy their effects, and bury them under our own sins and selfishness and pride and lust so that we feel them less and less. And when we do get struck with a strong movement of God’s Grace, if He means to be particularly merciful, it shows us all the horror of our sins more clearly than we ever saw them before, by comparison with the effects of this mercy. The unhappiness of our sins shows up with all the more ugliness compared with the beauty of the joy we feel for one instant of God’s Grace.

Iglesia y plaza de Santa Ana.

Tomado de Run to the Mountain. Edited by Patrick Hart, O.C.S.O., HarperCollins e-books, pp.203-219

-el-camaguey.jpg)

Comentarios

Heberto Casas Rivas

1 añoA great description of our province.